Florida's Emancipation Day

Emancipation Day

Emancipation Day is celebrated on May 20 in Florida. That’s the day that Federal troops entered the city of Tallahassee and accepted the surrender of the state. A Proclamation announcing the freedom of all enslaved people in the state was read from the steps of the Knott House. Eleven days after the end of the Civil War and two years after President Lincoln’s issue of the Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved people in Florida were liberated.

A receipt from September 19, 1862 for the sale of enslaved people

Image Source State Archives of Florida

Antebellum Florida

Slavery was present in Florida since the 1500s, with the Spanish occupation. They brought enslaved peoples from Africa. Slavery continued through the French and English control and through Florida’s entry into the American Union.

Florida’s antebellum economy was a mix of farming and shipping industry. Most enslaved people worked at the large plantations, owned by the wealthy planter class. These plantations were usually located in the middle of the state, away from the coast.

Civil War

Florida was the third state to officially secede from the Union. The vote occurred at 12:22 PM on January 10, 1861 with the results skewing 62 against 7. Of the 69 men that voted, 51 were slave owners. Some were extraordinarily rich (E. E. Simpson of Santa Rosa with $2.5 million in property, or about $80 million today) while others had less than $1000 in property (around $30,000 today).

In 1860, Tallahassee was a teaming town, with five churches, two newspapers, fifty stores, and twenty lawyers. Its citizens went to the local horse races, theatrical shows, and spring festivals. The city had a population of 1,932 (997 white, 889 enslaved, 46 free black). Tallahassee’s economy structure was similar to other Florida planter cities. Leon County had a population of 10,397 in 1860. Of that number, 8,200 were enslaved. The remaining 2,197 were white. This disparity of race is one of the largest in the South. Most of the slaves lived on large plantations, while most of the white men of the area were farmers or plantation owners.

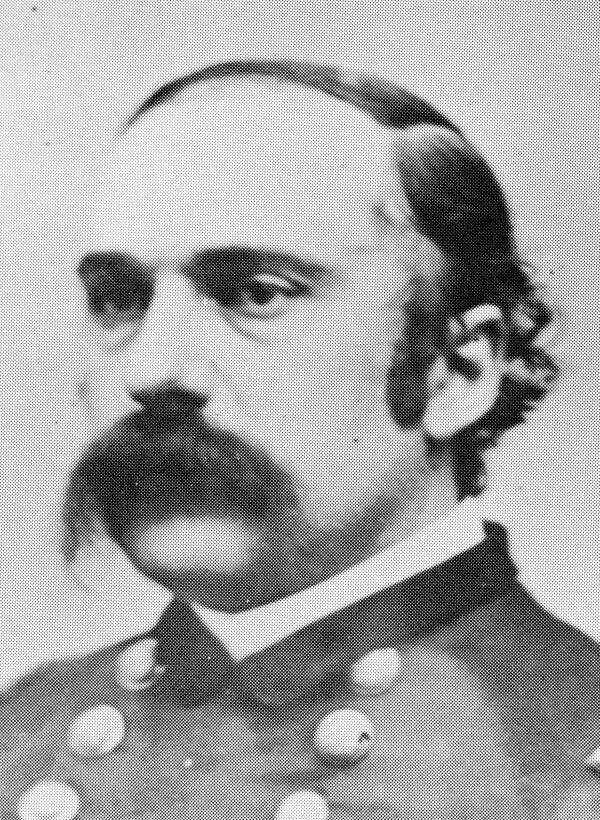

Members of the 1861 Secession convention for Florida

Image Source: State Archives of Florida

The rest of the state had a slightly different makeup than the “Cotton Belt.” The total statewide population according to the 1860 census was 140,424. Around half, or 77,447 were white and 62,677 were black (with only 932 being free men and women). Only one third of the white population were slave owners. While not the majority, plantation owners tended to have the power and status throughout the state. They were often supported by smaller planters who voted the same as the plantation class in hopes of joining them one day. Many residents of the port cities were transplants from the North and had more interest in shipping than agriculture.

Compared to other Southern states, Florida was not as important politically and economically to the secession and civil war. It was the smallest state in the Confederacy by population (only 16,000 white men were of age for military service). Many residents seemed to think that the Civil War would be bloodlessly succinct. Florida soldiers had been fighting the Seminole tribe off and on (and as recently as 1858) creating a blithe outlook.

Richard Keith Call, the former territorial governor, was against secession. He foretold the destruction of the state by saying, “Yes, you have done it! You have opened the gates of hell, from which shall flow the curses of the damned which shall sink you to perdition.” At the end of the Civil War, Florida had lost. It’s economy was devastated and thousands had died.

Not every city in Florida joined the Confederacy—Key West mostly stayed loyal to the Union and its fortresses stayed intact. Pensacola fell to the Union in 1862, it became an enclave to escaped slaves who secured their freedom before Tallahassee surrendered.

The Emancipation Proclamation

Scene in the House on the passage of the proposition to amend the Constitution, January 31, 1865.

Image Source: Library of Congress/Harper's weekly, v. 9, no. 425 (1865 Feb. 18), p. 97.

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. It is a stunningly brilliant piece of legislation because it freed all people who were enslaved in the Confederacy by the words “I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.”

While the proclamation had no immediate effect in the Confederacy, it gave power to the Union troop power to liberate peoples, disrupt the labor economy, and seize property. It also hindered the Confederacy’s ability to create alliances with European powers who had turned against slavery.

The Confederacy fell when General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Each Confederate state also surrendered to the Union in turn. The state of Florida learned of Lee’s surrender a week after it happened.

The Emancipation Proclamation led to the introduction of the 13th Amendment, which states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” It gave the U.S. Government the ability to enforce an anti-slavery stance.

State surrender

On May 10, 1865, Brigadier General Edward McCook and his troops were set up outside of Tallahassee. The state of Florida had officially surrendered at the end of April on the battlefield and McCook had arrived in the state to systematically enforce the Emancipation Proclamation and set up a new state government. McCook left most of the 500 soldiers at the edge of the city and rode into Tallahassee with a small group of officers to greet city officials and accept the official (civic) surrender of the state.

Union commanders and federal troops began to inform enslaved people of their freedom in a systematic fashion. Leon County plantation owners were instructed to read the proclamation on May 19. On May 20, McCook had the American flag flying above the Old Capitol Building. McCook set up at Thomas Holmes Hagner’s house (present day Knott House) and on May 20, with the Third United States Colored Infantry at his side, he read the Emancipation Proclamation to the city of Tallahassee. Confederate troops were paroled, and military equipment was surrendered. Federal troops led the celebration by playing “John Brown’s Body.”

Notice in the Floridian and Journal, May 20, 1865 regarding the Emancipation Proclamation

Image Source: Museum of Florida History

By the end of May, Florida had been liberated.

Things were a bit different in Texas. Many telegraph lines had been destroyed during the Civil War, so news took longer to reach all outposts in Texas (Gen. Gordon Granger would not reach Galveston, Texas until a month after Tallahassee surrendered). So, while Juneteenth is celebrated as the day enslaved people in Galveston learned that had been freed, Florida’s Emancipation Day is officially May 20. Both days can be celebrated of course!

Emancipation and Celebration

In 1865, newly freedmen and freedwomen met at Bull’s Pond to celebrate with an impromptu picnic (Bull’s Pond has since been renamed Lake Ella).

The next year (1866), on the first anniversary of their liberation, the Freedmen’s Benevolent Society led a parade with pipes and drums down the city. The year after that (1867), another day long picnic and political rally was held at Bull’s Pond. It was attended by 2,000 former enslaved people. In 1871, the picnic was hosted by Reverend Charles H. Pearce and A.M.E. Church.

Other celebrations were held at Horseshoe Plantation in the 1930s. Other than picnics and parties, there is a tradition at the grave of Union Soldiers buried at Old City Cemetery. Their graves are decorated in a tradition that dates to around 1871.

Leon County became the first county in the state of Florida to recognize Emancipation Day as a county holiday in a unanimous vote. The City of Tallahassee followed and recognized May 20 as Emancipation Day.

Standing in front of a decorated car for the 1922 parade - Saint Augustine, Florida.

Image Source: State Archives of Florida/Twine

African American workers and tenants celebrating Emancipation Day (May 20th) at Horseshoe Plantation. 1930 (circa).

Image Source: State Archives of Florida

Reenactors recreate a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation at the Knott House Museum in Tallahassee in 2015. This was the 150th anniversary of the original announcement.

Image Source: State Archives of Florida/Brockmann

Interesting Links:

Juneteenth marks the date of June 19th, 1865. which was when the Emancipation Proclamation was first read in the state of Texas. Texas was the last Southern state to officially read the Proclamation. Juneteenth is not currently recognized as a national holiday, but it is a designated holiday in six states.

Juneteenth is a day of observance for the entire state of Florida. If you’d like to know more about the difference between Juneteenth and Florida’s Emancipation Day, the Florida Archive has a quick recap.

This guide from the State Library of Florida explores Emancipation in Florida and the Reconstruction period that followed (1865-1877). There is also a portal with books, articles, state archives, and federal archives.

Citations:

“The Emancipation Proclamation.” The National Archives.

“Emancipation and Reconstruction in Florida.” State Library of Florida.

Gaffney, Robert. “Proposal to Recognize Juneteenth As State Holiday Advances Past the First Committee Stop.” WFSU

Gaffney, Robbie. “Tallahassee City Commission Designates Emancipation Day As Paid Holiday.” WFSU

Hare, Julianne. Tallahassee: A Capital City History. Arcadia. 2002

Introduction: 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution . Library of Congress.

“Juneteenth and Emancipation Day in Florida.” Florida Memory (State of Florida Archives).

Kenneson, Claude. “Florida’s Emancipation Day and Why It Matters.” Tallahassee Historical Society.

“Leon County becomes first county to declare Florida Emancipation Day a holiday.” WTXL

Records of southern plantations from emancipation to the great migration. Series B, Selections from the Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries [microform] / general editor, Ira Berlin, microfilm reels.

Revels, Tracy J. Florida’s Civil War: Terrible Sacrifices. Mercer University Press. 2016

Russell, Leon W. and Adora Obi Nweze. “Florida: Let’s be historically correct about our Emancipation Day.” Tallahassee Democrat.

“The War Ends: Surrender, Occupation, and Emancipation.” Museum of Florida History.

“Thirteenth Amendment.” U.S. Congress.

“Twentieth of May: Emancipation in Florida.” Museum of Florida History.